Maritime History

The maritime history of Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary encompasses much of New England's history. As the Ice Age glaciers began retreating from what is now eastern Massachusetts around 16,000 years ago, portions of Stellwagen Bank and Jeffreys Ledge were dry and home to grasses, forests, and Pleistocene animals. It is possible that between 11,000 and 12,000 years ago, Paleoindians inhabited these areas and exploited the rich marine resources found along the shore. Rising sea levels slowly inundated Massachusetts Bay, pushing native peoples to settlements along the current shoreline. For thousands of years Native Americans utilized the vast fish and shellfish resources of Massachusetts Bay, developing rich cultures that were supported by the marine environment.

During the thousands of years of human occupation of the Massachusetts coastline, waterborne transportation was an essential part of the region's communication network. Vessels of many shapes and sizes carried a variety of cargo and multitudes of people to and from Massachusetts ports. Beginning with the native peoples and continuing with the earliest colonists who cut settlements from the thick forests and fished along the shore, New Englanders have derived tremendous economic benefit from their close association with the sea. New Englanders traveled the breadth of the globe in sailing ships, trading with far flung cultures or harvesting the bounty of the sea. At the beginning and end of each voyage, many of these intrepid mariners crossed through the waters that are now recognized as Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

Whaling to Watching

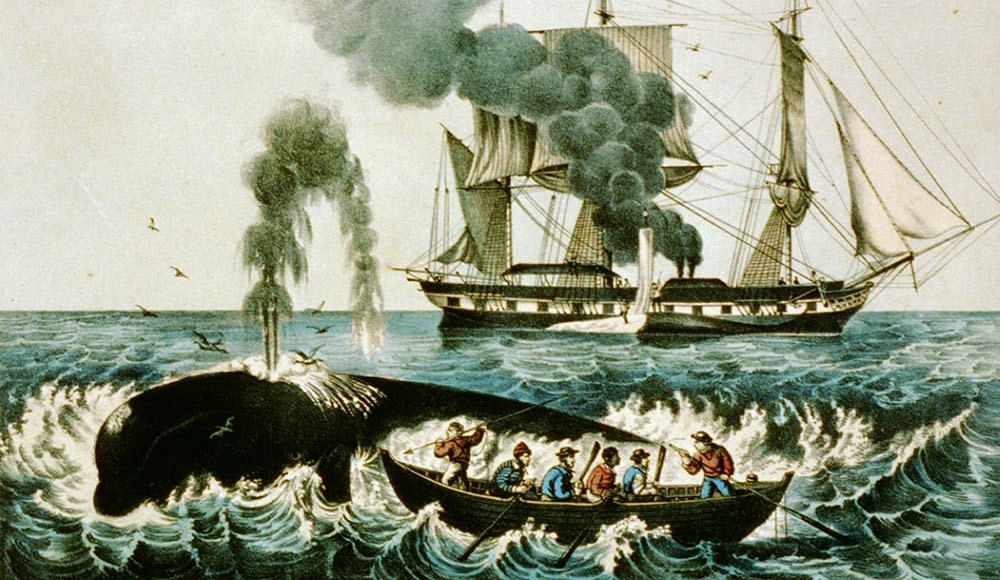

Whaling played an important role in the maritime heritage of New England. In the late 1500s, Basque whalers came to the New World, possibly as far south as Stellwagen Bank, but it was not until the 17th century, with shore based whaling in Massachusetts Bay, that whaling became a common activity along the East Coast. Small boats set out from the shores of Cape Cod in pursuit of North Atlantic right whales. Once harpooned, the whales were killed with a lance and then towed ashore where their blubber was rendered into oil. These activities hastened the decline of the North Atlantic right whale population, which now is considered critically endangered.

Today, whales are viewed in a different way. From April through November, people board whale watching vessels to view these animals up close to appreciate their grace and power. Stellwagen Bank is one of the best places to observe feeding humpback whales in the United States and even worldwide. Whales in the sanctuary are no longer hunted; rather they are studied and enjoyed for their beauty and role in the ecosystem.

The Charles W. Morgan, the last surviving wooden whaleship, embarked on its 38th voyage in the summer of 2014 (nearly a century after its last whaling trip) and sailed into the sanctuary on a mission to raise awareness for whale conservation.

Links

The Charles W. Morgan Sails Again

The Charles W. Morgan sails with the whales on Stellwagen Bank

Earth is Blue: Charles W. Morgan Tour

The 38th Voyage of the Charles W. Morgan

Whaleship Charles W. Morgan to visit Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary

All Aboard

Passenger traffic across Massachusetts Bay steadily built from the 17th century to the 19th century as New England's economy and population grew. As the largest U.S. city closest to Europe, Boston became a destination for many immigrants, but travel by sail was an uncertain affair. Prior to the institution of regularly scheduled sailing packets in the early 19th century, travelers might have waited weeks for their vessel to fill its hold or its cabins. Once started, these trips often lasted much longer than anticipated since even the fastest vessels could become oceanic prisons when the wind stopped blowing.

Later in the 19th century, the application of steam propulsion dramatically transformed passenger travel. Passengers could now count on a departure time and journey length. Additionally, steamships were built with comfort in mind. Passengers enjoyed lavish meals and warm beds en route to their destinations. Today, thousands of people cross Massachusetts Bay on high speed ferries that connect Cape Cod to Boston and on cruise ships that depart Boston for Bermuda, the Caribbean, Canada, and other ports along the New England coast.

Into the Hold

A tremendous variety of vessels and cargos have passed through the sanctuary's waters. Whether a colonial brig trading between Salem and Jamaica or a clipper ship carrying tea from China, foreign commerce was the lifeblood of New England until the American Civil War.

After the Civil War, coastwise shipping of bulk commodities became the focus of New England's merchants. Carried on schooners, the American coasting vessel of choice since colonial times, cargos of granite, fish, and ice left Massachusetts Bay. Returning to New England, the schooners carried coal and lumber, flour and iron ore. While the era of sailing ships is long gone, Boston remains a busy port frequented by container ships, tankers, tugs, and barges.

Bounty of the Sea

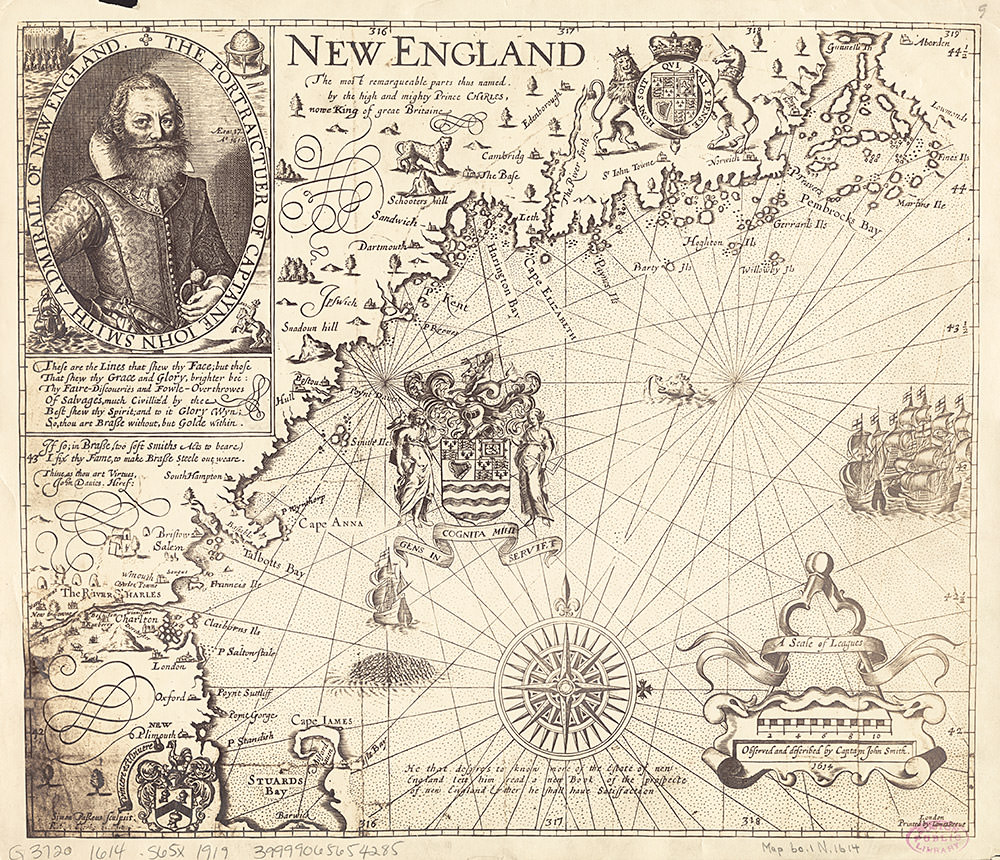

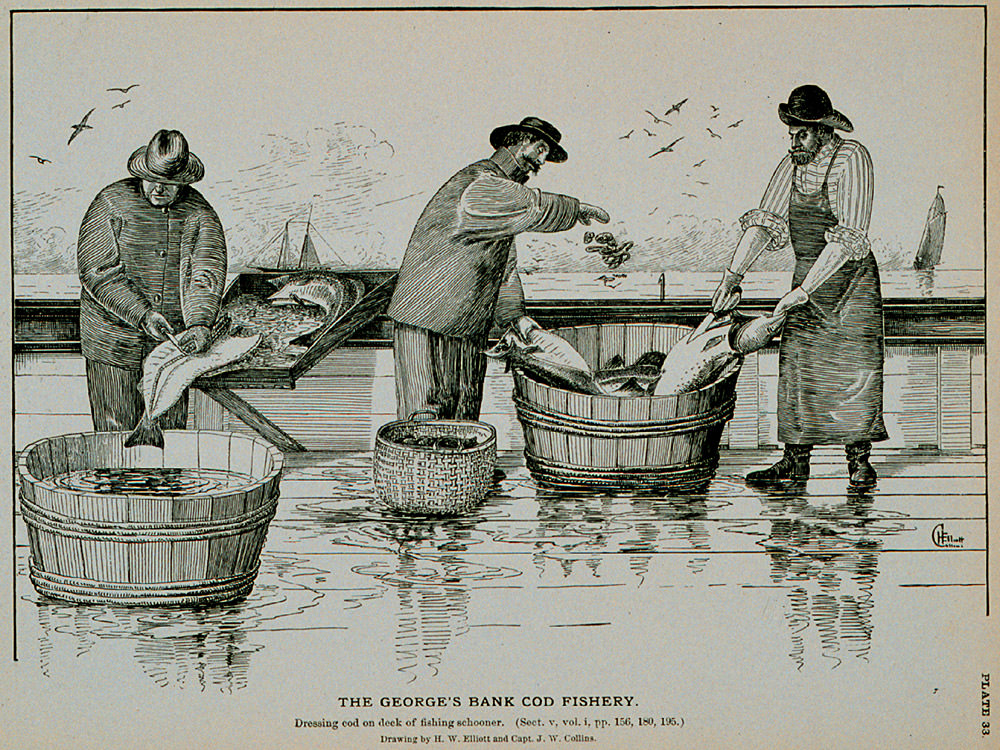

For over 400 years, Massachusetts Bay has been a center for fishing activities. The area was first fished by Native Americans who collected a variety of marine foods along the water's edge. During the later colonial period, fish played a large role as one of the region's main export commodities. Captain John Smith (famous for his associations with Pocahontas and the Virginia colony) explored and mapped the coastline in an area he labeled New England. His 1616 and 1635 maps placed a sailing vessel and a mound of fish heads over an area that approximates today's sanctuary. The Pilgrims, most likely influenced by that map and other explorers' reports, came to the Plymouth colony with the intention of fishing.

America’s oldest fishing port is Gloucester, Massachusetts, first settled in 1623. Many 17th century towns grew and prospered from this industry. As technology progressed, fishing vessels and fishing methods evolved to meet the demands of the market. The small rowed crafts of the colonial period were replaced by swift schooners in the 18th and 19th century, which were then replaced by engine driven trawlers in the 20th century. Today, fishermen still travel from their home ports for Stellwagen Bank to harvest finfish and shellfish.

War and Peace

The waters over and around Stellwagen Bank have been the scene of conflict several times during past centuries. Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 privateers, rum runners, and German submarines have all navigated the waters of Massachusetts Bay. The vitality and economic importance of Boston have attracted these less than peaceful activities. Patriots, outlaws, and enemy forces have all used the waters over and around Stellwagen Bank for attack and refuge.

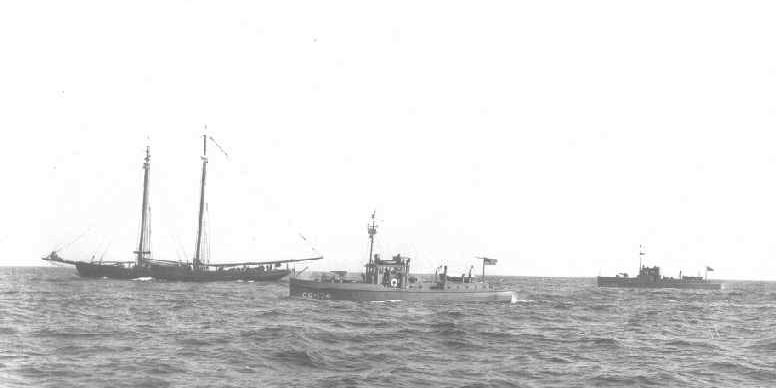

During Prohibition, many entrepreneurs converted a variety of vessels for smuggling liquor. This lucrative but illegal "rum running" business involved larger vessels that anchored in Massachusetts Bay and transferred the alcohol into smaller craft that would carry the contraband products to shore.

In October of 1924, a U.S. Coast Guard squadron based in Boston discovered more than a dozen vessels waiting on Stellwagen Bank to have their illegal cargo offloaded. After some resistance, the Coast Guard captured the smugglers and their vessels, but not before the rum runners tossed 850 cases of brandy, champagne, and whiskey overboard. This scene repeated itself several times throughout the 1920s, as the relatively shallow water over Stellwagen Bank was an ideal place to anchor.

Time Capsules on the Seafloor

Located at the mouth of Massachusetts Bay, Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary sits astride the historic shipping lanes and fishing grounds for Massachusetts ports such as Boston, Gloucester, Plymouth, Salem, and Provincetown. These ports have been centers of maritime activity in New England for hundreds of years. Over time, accidents have occurred and ships have sunk, leaving virtual time capsules on the seafloor. As a result, the sanctuary has become a repository for the nation's maritime heritage resources, with shipwrecks serving as discrete windows into specific moments of our sea-going past.